Runaway, unwinnable competition for social status puts us all in a killer race to the bottom.

In his book, The Darwin Economy: Liberty, Competition, and the Common Good, economist Robert H. Frank makes the bold assertion that in 100 years, economists will cite Charles Darwin — not Adam Smith — as the father of the discipline.

Frank writes:

Darwin was one of the first to perceive the underlying problem [with markets] clearly. One of his central insights was that natural selection favors traits and behaviors primarily according to their effect on individual organisms, not larger groups.

Darwin observed this problem in nature, noting that natural selection often favored mutations that benefited individuals relative to the rest of their species, but harmed the species as a whole. These cases reflect the burnout that characterizes our current moment.

In “We’re Optimizing Ourselves to Death,” I illustrated how the prisoner’s dilemma — a well-known economic thought experiment — explained the millennial generation’s obsession with self-optimization. In this essay, I take it a step further, using Darwin’s observations and insights to illustrate the roots of burnout culture and what comes next.

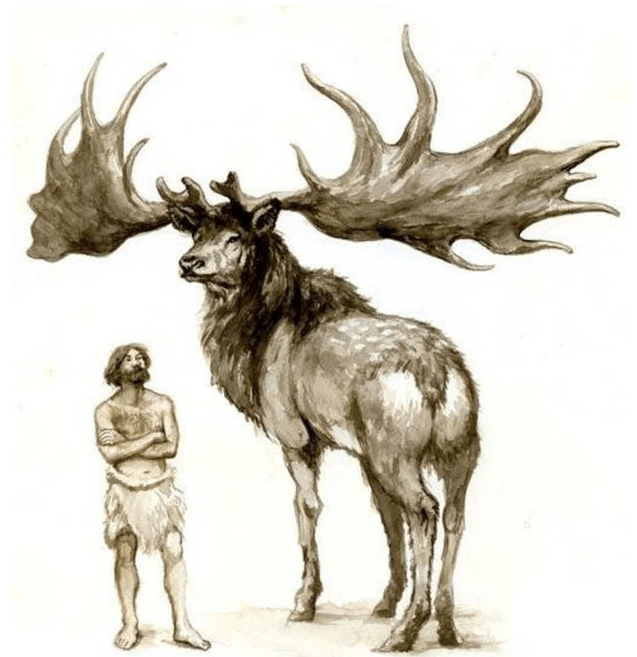

To begin, it’s first necessary to understand how Darwin’s observation about the fallibility of free markets applies to an extreme example: elk. Male elk, otherwise known as bulls, carry some of the largest antlers in the animal kingdom, measuring up to four feet across.

During mating season, bulls with the largest antlers battle over mates. These battles often last for hours, leaving both the winner and loser battered and exhausted. Winning, though, is worth it. The victor earns status that grants him outsized access to dozens of fertile females. It follows that a mutation coding for larger antlers would be useful to an individual bull, allowing him to dominate others in battle and pass his genetic material along to the larger population.

The caveat is that eventually, most bulls’ antlers would be approximately the same size as those of the bull with the original mutation. At that point, the advantage its mutation once conferred — because it was dependent on the antlers’ relative size, as opposed to their actual size — would disappear. Further, the mutation would actually be harmful to the larger population of bulls, as the size and weight of their antlers would hinder their efforts to escape their natural predators in the densely wooded areas both occupy.

As Frank notes in his book, bulls would be better off if they could all agree to halve the size and weight of their antlers. Doing so would make them less susceptible to predators, for one. Even the elk with the largest antlers, who has the most to gain from antler size, wouldn’t oppose the halving; it is their relative size, after all — not their absolute size — that matters in battles over mates.

Of course, this agreement would be impossible to implement in practice. The only way it could work is if an elk with smaller antlers beat one with larger antlers in battle. Even if this did happen — and it never would — it would be a fluke. The following mating season would bring another battle and a male with larger antlers that would once again capture the lion’s share of mates.

The broader point is that there is no feasible way for elk to self-regulate away the most harmful effects of runaway, in-species competition for status, and in turn, mates.

As we’ll see, the same is often true for humans.

Consider the doping scandal that rocked professional cycling several years ago. After years of denying wrongdoing, Lance Armstrong admitted to having undergone performance-enhancing treatments, otherwise known as doping.

According to Armstrong, because of how widespread doping had become in professional cycling at the time, he didn’t feel he’d done anything wrong.

This rationalization seems absurd on the surface, but makes sense in practice. In sports, as in nature, objective performance means nothing — what matters is performance relative to the competition. If every cyclist in the Tour de France had been doping, Armstrong still would’ve been the best in the field relative to everyone else.

Now, in theory, if everyone in professional cycling were doping, Armstrong’s behavior wouldn’t have been an issue. Athletes have always sought ways to improve their performance relative to one another. Many of them are legal and openly used. The problem with blood doping is that because the process thickens the blood, it’s associated with an increased risk of heart disease, stroke, and cerebral or pulmonary embolisms.

Put another way, all cyclists would be better off if they collectively agreed not to do it.

This coordination would never work, however. This is an example of what economists and political philosophers call a collective action problem, in which all individuals would be better off cooperating, but don’t because conflicting interests between individuals discourage it. In the context of professional cycling, the incentive for each individual to win outweighs their incentive to not dope, even as the consequences for doing so include potential loss of life.

Burnout, then, is perhaps best understood as a collective action problem at scale.

We are wrongly convinced that the status symbols prior generations sought — college degrees, home ownership, and more — are those we should seek, too. The ever-rising costs of the behaviors we perform to obtain these status symbols are causing our generation to burn out, if for no other reason than that by performing them, we’re quite literally spinning our wheels and going nowhere.

These behaviors take many forms. We take out six figures of debt to get degrees we don’t realize aren’t objectively valuable until we’re six months into a job search without prospects. When we finally land one, we drink coffee or take Adderall — often to tolerate ourselves in its context — then drink meals from bottles to maximize limited hours of heightened productivity.

And the problem with these behaviors isn’t necessarily that they can’t work. Like doping did, they might have — at least at first. But the advantages they once conferred were based on the relative scarcity of the behavior being performed. Once everyone caught up, they disappeared, leaving only their costs — anxiety, sleeplessness, or crippling amounts of debt — behind.

Put another way, once everyone’s on Adderall, no one is — and everyone’s worse off.

Our performance of these behaviors resembles those of both elk and professional cyclists under unregulated, runaway competition, and illustrates what’s known among evolutionary biologists as the Fisherian runaway.

This phenomenon explains how once useful traits become absurdly exaggerated — and thus, extraordinarily costly to display — under runaway competition.

Examples abound in both nature and society, from the elk’s massive antlers to the abuse of PEDs in professional sports. These cases illustrate situations in which natural selection favors traits that benefit individuals in competition with their own species — most often over status or mates — but objectively harm both the species’ individual members and the species as a whole.

The selection process occurring within our accelerated society reflects this process. Optimizing individually improves our status relative to everyone else, but it only actually improves our lives — and by extension, society’s well-being — if doing so is viewed in the context of what we’re optimizing to achieve. Often what we’re seeking is what society has conditioned us to believe is valuable — even if, like the massive antlers of the elk, it no longer is in reality.

The ability to display these signals, then, is a pyrrhic victory. We’re “higher status” than we were before, but we — like the elk and doped-up professional cyclists under runaway competition — are objectively worse off.

More than 150 years ago, the British philosopher and political scientist John Stuart Mill proposed a solution to the collective action problem, including the grounds on which it could be justifiably used.

In On Liberty, Mill wrote:

The sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self-protection.

Mill’s argument is that it’s only permissible to limit an individual’s freedom when there’s no less intrusive way to prevent harm to others.

In the case of professional cycling, there was no less intrusive way to prevent cyclists from harming themselves than by instituting a complete ban on doping. Without an external body to regulate it away, the incentive for each individual to do it would’ve been too high.

Crucial to understand about this — and part of what Darwin would have seen so clearly — is that absent a mandate from a governing body within professional cycling, it would’ve been completely rational for individual cyclists to continue doping.

Like elk battling over mates, cyclists value the status that accompanies winning — even as they know it to be associated with an increased probability of death — more than what they see as failure. It’s only once they know doping could mean never having the chance to win again that the scales tip towards balance.

To be clear, I’m not arguing for more government. I’m simply reiterating that governing bodies — in whatever form they take, and there are many — should only regulate to protect us from the worst effects of competition with each other.

Frank puts it best in his book, writing:

Failure to understand why markets fail has led many on the left to invent spurious explanations for why we need to regulate them. Their claim is that regulation is necessary to protect us from exploitation by sellers and employers with market power. But the real reason we regulate is to protect ourselves from the consequences of excessive competition with one another.

Burnout is a result of excessive, runaway competition between individuals. Winning this competition boosts individuals’ status relative to one another, but harms both individuals and society as a whole. It thus appears to carry the characteristics of a problem solvable through regulation.

The problem with this diagnosis — and the consequent prescription — is that we aren’t cyclists on a course. The game we are playing has no beginning or end; there is no finish line. We cannot see the 8 billion people playing it anymore than we can sit them down and explain to them why the decisions they’re making are suboptimal.

And so, inevitably, our wheels continue to spin, grasping for ground that no longer exists.

The fate of the Irish elk — one of the largest elk species to have ever lived, and an ancestor of those that exist today — offers a final metaphor through which to understand burnout.

Similar to the elk of today, Irisk elk with the largest antlers relative to the rest of the population had an advantage in fights with other bulls over mates. Thus, the Irish elk evolved to have massive antlers that were useful in these fights, but restrictive to their owners in other respects — like, say, when trying to escape a predator.

As a result of their antlers, Irish elk would often trap themselves in brush, making them easy targets for predators. Evolutionary biologists hypothesize that this led to their extinction.

The long-term evolutionary argument about burnout, then, is that it’s a form of extinction — not of people, but of signals.

Those we once competed for — degrees, home ownership, and more — are no longer the insurance policies against failure they once were. The sad truth to admit is that those of us who’ve failed to realize it — which is to say, all of us — are those for whom burnout isn’t a temporary condition, but a way of life.

Put another way, a recent college graduate with six figures of student debt and no job prospects could no sooner offload that debt than an Irish elk could offload its antlers.

And so it may be that the best way to deal with burnout, as others have suggested, is simply letting it exist, and acknowledging that the things we once competed so hard for do not matter as much as we thought. This is a painful thought; we all know people mired in debt, staring into a future in which the only certainty is having to pay it off. But it is the reality.

As we acknowledge it, we may also begin to recognize the new status symbols emerging around us — those that will mercifully allow the generations that follow us to live lives defined by the meaning they’ll take from them, instead of the burnout too many of us already have.

That is, until they burn out, too.

Liked it! It is so fun to read your writing. You ARE a write! It is part of you. Do not let yourself burn out. Your antlers are plenty big. And unlike the elk…you can decide how big they need to be; what is optimal for you. I love you. I do hear from people like the martinelli’s that some of your generation say they do not want the big house. Could be the expense in the bay area, not that they really don’t want it. Also hear you do not want expensive/nice furniture…preferring throw away Ikea stuff. Lastly…car ownership seems to be less interesting…given Uber and the future of fractional ownership.

LikeLike

I would rather not be remembered than remembered for the nothing we spend our lives attaining… People these days are, as you say, spinning their wheels to no end and racking up ephemeral and superficial rewards – titles, promotions, awards. We should all take a moment step back and try to remember why we exist (why we were created, if you let this statement pass on an article about Darwin) and work on the one thing we can truly call our own – the soul. Everything else will perish, whether you lived this life as the Prime Minister or as a pauper. But alas, we are far too busy and important these days to take pause. Keep spinning those wheels till you’re spinning in the grave.

Just my 2c.

LikeLike