Why every purchase is a performance

“I am not who you think I am; I am not who I think I am; I am who I think you think I am.” — Thomas Cooley

About a month ago, I published what has become my most trafficked piece ever: “People Don’t Buy Products, They Buy Better Versions of Themselves.” The article explained why the “Pepsi Generation” advertising campaign was so successful. As I wrote:

The Pepsi Generation was revolutionary because it was the first time a brand convinced people to purchase their product by focusing on the type of person that doing so made them…[it was the first brand that focused on] selling not a product, but a better version of ourselves.

Yet it is the last part of that statement that is worth examining, especially in the context of the Thomas Cooley quote at the beginning of this essay.

Put simply, a “better version of ourselves” is almost impossible to distinguish from a version of ourselves that we think other people will approve of. The Pepsi Generation is a perfect example of this: The campaign never would have worked without first convincing people that others would see them in a way they’d imagine others would approve of — youthful, anti-establishment, rebellious — if they drank Pepsi.

In his essay, “Ads Don’t Work that Way,” writer Kevin Simler of Melting Asphalt calls this phenomenon cultural imprinting. In his words:

Cultural imprinting is the mechanism whereby an ad, rather than trying to change our minds individually, instead changes the landscape of cultural meanings — which in turn changes how we are perceived by others when we use a product.

This quote almost nails it, but there’s more to it. It isn’t just that cultural imprinting changes how we are perceived when we use a product, rather, cultural imprinting changes how we believe we are perceived when we use a product. More importantly, cultural imprinting changes how we believe we are perceived not just when we use products, but when we do anything. It just so happens that in the consumptive economy we live in now, “consuming” — sustenance, media, etc. — is most of what we “do.” So, framing the issue in the context of the products we consume makes sense.

The idea that cultural imprinting changes how we believe we are perceived when we do anything relies upon another idea Simler refers to in the essay: common knowledge. This is the concept that people in society not only know things, but also know and trust that other people also know those things. This idea appears everywhere — from the infrastructure that frames our economies, to the advertising that frames our consumptive behavior, to the social norms we all agree to abide by.

The parallels between these three contexts — infrastructure, advertising, and social norms — are worth examining. Let’s take each in turn.

Infrastructure: Road Rules

Roadways emerge spontaneously in a society. They also create common knowledge over time by facilitating repeated interactions between drivers. In the U.S., for example, you drive on the right side of the road. Everyone who drives knows this — but more importantly, everyone who drives knows that everyone who drives knows this. If no one trusted that other people knew, no one would drive.

This kind of common knowledge, often formalized by laws and infrastructure, alerts people to how they can expect others to behave in the context of a system. If I’m driving around a blind curve, I can expect that someone coming from the opposite direction will do so on the other side of the road.

A road that offered no feasible way for drivers to anticipate the behavior of other drivers — especially in a situation like a blind curve — would not be used for long. If it were, it would be lined with signage (“blind curve/road narrows, please proceed with caution”) and barriers (walls, tolls, etc.), like those in countries whose infrastructure was designed prior to the invention of the car (Scotland comes to mind). More likely, a road like that would be widened or otherwise renovated, or simply rebuilt elsewhere. The same is true for products.

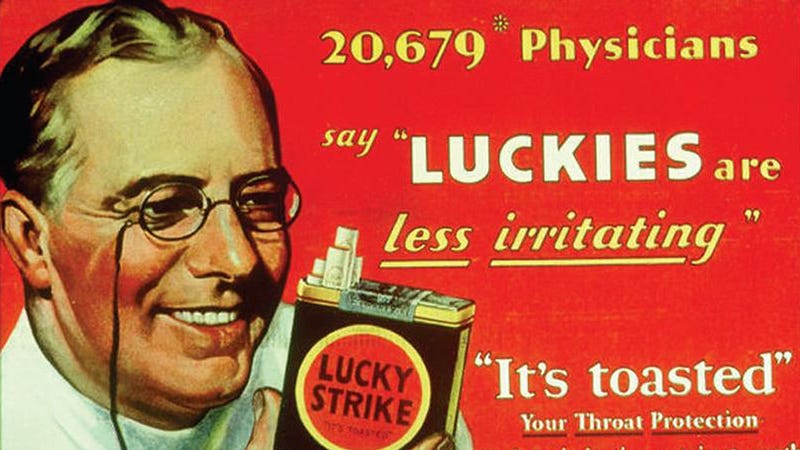

Advertising: Cigarettes Aren’t Bad For You…Or Are They?

For years, Big Tobacco convinced people that cigarettes were not only safe, but healthy, relying in many cases on fringe research presented as fact. This allowed people to ignore the reality that cigarettes were, in fact, toxic and directly linked to cancer. It also allowed Big Tobacco to continually create positive common knowledge around cigarettes such that people believed that they were being perceived in a positive light when they smoked.

Gradually, research eroded this perception. But even as it became clear to a majority that cigarettes were unhealthy, it was not yet clear to consumers that it was clear to the majority that cigarettes were toxic. It wasn’t until the research was presented in such a way that negative common knowledge began to emerge around the cigarette that the message got a foothold. In his essay, “The Age of Distributed Truth,” writer Eugene Wei describes this as the “tipping point,” when knowledge that was once locally common becomes globally common. The tipping point for cigarettes was the moment when everyone realized that everyone knew they were toxic.

One of the most notable campaigns to create negative common knowledge around the cigarette was the “Tips From Former Smokers” campaign. This campaign did exactly what Simler outlines in his essay: it showed the results of smoking, and thus indirectly convinced people that they shouldn’t smoke by showing them exactly what they would become — and thus, how they would be perceived — if they did.

Of course, people still smoke cigarettes. But like Scotland’s narrow, pockmarked roads, the packs they purchase are lined with warnings about the dangers of smoking. They’re also only accessible to those of a certain age, and they’re taxed — especially in places like New York, or California — at such a high rate that people will cross borders to find alternatives. If smoking is to have a future, it likely won’t be with the cigarette, and the negative common knowledge created around it is entirely to blame.

Social Norms: Kevin Spacey’s Billionaire Boys Club Goes Bust

This past weekend, the last movie Kevin Spacey filmed prior to the revelations about his deeply inappropriate sexual behavior towards dozens of colleagues, Billionaire Boys Club, was released. The film grossed $618 in its opening weekend. $618. That is not a typo. In the context of common knowledge, I’d argue that this paltry opening has nothing to do with the objective quality of the film, but rather with no one wanting to be seen as the person they believe people would perceive them as if it were known that they paid to watch a movie starring an accused serial sexual abuser. Further, I’d argue that this film will do moderately well once it moves out of theaters, as those who are curious — but not curious enough to risk being perceived as Spacey sympathizers — will watch it in their homes, out of sight of the approval economy.

Now that we’ve seen how both the deliberate and organic creation of common knowledge can inspire inaction, it’s worth examining how it can inspire action. One great modern example is The New York Times.

Prior to recently, the Times had been plagued by lagging growth and declining readership. Trump, however — and more specifically, the Times’ reaction to Trump — has given it life, in no small part due to an advertising campaign released in the wake of his presidency: “Truth Is Hard”. This campaign created some of the most potent common knowledge ever.

Readers of the Times, the campaign promised, would be perceived as a part of a group that was transcending Trump’s Truthless America. Thus, to read the Times was to believe that if you were seen reading it, you would be perceived as an intellectual, someone “smart” enough not to be compelled by another populist outburst or hate-fueled rant. This is the approval economy at work. It’s the idea that readers knew — and aspired to become — the people they believed others would see them as if they were spotted reading the Times.

It should come as no surprise that the most famous advertising campaigns of the last century all resemble one another; each one has succeeded by convincing people that others would see them as the people they wanted to be perceived as after purchasing the product. What is our perception of ourselves, after all, if not a blend of our experiences, our reactions to them, and our understanding of the consequences of those reactions? The last part here is the most important, especially now. As I argued in “People Don’t Buy Products, They Buy Better Versions of Themselves”:

Social media is well-understood to be contributing to identity politics, but I’d argue it’s contributing to something deeper: identity paralysis. This condition is one in which we have a forced awareness of how everything we say and do — even the seemingly inconsequential, like the shoes we wear, or the airline we fly — reflects on us. It follows that our generation would also be uniquely drawn to brands that make us feel how we want to feel about ourselves, even as how we want to feel about ourselves is often nothing more than how we want to be perceived externally.

Put another way, it has become almost impossible to detach any action from the external approval that will accompany it. In each of these examples, common knowledge about the product makes or breaks its success. All advertising campaigns are drastic accelerations of the normal pace by which common knowledge is accumulated. They can quickly convince many people of how they will be perceived in the context of a brand — either as someone they want to be (enlightened truth-seeker that subscribes to the Times), or someone they clearly do not (corpse in a totaled car/woman in the “Tips From Former Smokers” ad/supporter of an accused serial sexual abuser). The magic of advertising is that it can convince consumers of all this prior to anyone actually owning or engaging with the product.

The most successful modern brands make one thing abundantly clear: approval is a hell of a drug. The best way to sell a discretionary good in a saturated market is to convince people that others will approve of them if they purchase that good. And in case it wasn’t clear, in our world, every good is discretionary, and every good exists in a saturated market. Crucially, this does not mean people don’t buy “better versions of themselves;” in fact, the opposite is true: purchasing a better version of ourselves is inextricably linked to purchasing a version of ourselves that we believe will afford us approval, or validate us.

It’s strange, then, that the most recognizable brands of this century — Facebook, Instagram, Twitter — are giving way to a world in which, per big data, it is easier and easier to sell products without stories or common knowledge. The algorithm doesn’t need to create a cultural narrative of perception, it can simply know that you’re a perfect candidate for _________ product because you’re __-years-old making __,_____/year with ______ skin and a _______ degree.

It’s almost poetic that these platforms have made themselves the same arbiters of approval that brands used to be (and in many cases, still are). Social media outlets, like brands, are lottery tickets that people “purchase,” albeit with their attention and their data, that in turn afford them the opportunity to capture a staggering amount of approval and consequent physical high if they win (and an equally staggering amount of disapproval and physical pain if they don’t). I know this to be true because the rush that has accompanied the unprecedented validation I’ve received in the past month from my story going viral is almost unlike any feeling I’ve ever known, and certainly any feeling I’ve ever gotten from a physical brand. It’s a hard truth to admit, but it’s the truth, and I’m admitting it — and I don’t think I’m the only one.

Like successful brands, social media succeeds because it is built to make people believe they are being perceived in the way they want to be perceived. In the approval economy, little else matters — and brands of today would do well to take note.

Like this? Click here to subscribe to my newsletter. You can also support me on Patreon by clicking here.

Roadways do not “emerge spontaneously in a society.” Every highway, even the Interstates, was once a wagon road, and an Indian trail before that, and a game trail before that. Road layout is dictated by terrain. Even the deer can figure that out.

LikeLike

Me thinks it was Charles Cooley (sociologist, 1864-1929), not Thomas Cooley (economist)

LikeLiked by 1 person